We all know that the internet is a dangerous place, with lots of bad actors trying to scam us, spam us, doxx us, phish us, and troll us. And then there’s Facebook. In many ways, however, the real cyberthreat comes instead from all the IT people ostensibly trying to keep us safe.

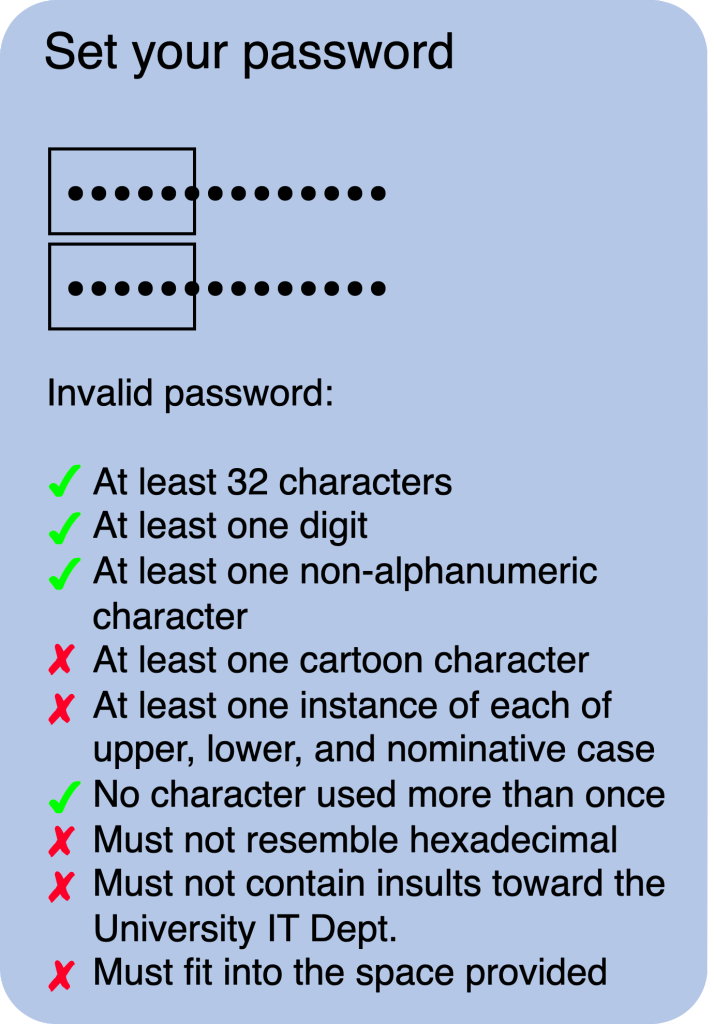

It all started out innocently enough with IT advising us to use stronger passwords before forcing us to use those ones with an LSD-induced mixture of big and small letters, digits, and random punctuation. You know, the ones that you can’t possibly remember without writing them down? (Or that Elon Musk is tempted to use to name his next kid?) And then you invariably do forget because you’re not supposed to write them down anywhere or can’t decipher the piece of paper that they’re on anymore in your paranoid attempt to sort of keep them secure? And then it doesn’t matter anyway because you’re forced to change them every three months? And the ones that you’re still being advised to use even though the guy credited for pushing that system on us publicly acknowledged it as being wrong (long passphrases being more secure than shorter gobbledygook) and apologized for it way back in 2017?

And then it goes downhill from there …

Another invention that someone probably should also be apologizing for in 20 years is two-factor authentication (2FA), where login attempts need to be confirmed through the use of a secondary, time-limited code that is sent to you via e-mail, SMS, or some authenticator program.

It’s not that 2FA is a bad idea as such but the implementations of it often seem designed more to frustrate legitimate users than any would-be hackers. Often, the codes simply don’t work. Or they get sent to you by e-mail when you have no access to it at that time. Most often, however, the frustration derives from having to wait an inordinately long time to get the code, making you unsure if the code was even sent in the first place. (So you ask for another. And another. And then they all arrive simultaneously.) Or the code gets sent by default precisely to that app you’re trying to log into and for which you need the code. But, for a prime example of a really moronic implementation of 2FA, we need only turn—rather unsurprisingly—to the University of Not-Bielefeld.

Slow to the game but nevertheless eager to still play along, the University’s IT Department has been steadily tightening the cybersecurity thumbscrews on us. So we too have those impossible-to-remember passwords as well as those banners inserted at the top of external e-mails warning us that they originate from outside the secure ivory walls of University, banners that have long since faded into background noise. We also get regular e-mail updates informing us of the latest cyberthreats (usually phishing e-mails) and that always end with the same sign-off of “Stay alert” that gets about as much attention as those warning banners.

But, in the wake of a cyberattack that almost took over the University’s servers in 2023, IT decided that it was time to install 2FA to log in to the University’s most critical of online services (e.g., webmail, VPN, or the teaching platform but not those for downloading copyrighted, licensed software or any of the millions of admin forms). The first step in implementing this late last year was to divide the single login pages into two separate ones, one for the username and a second one for the password. I still have absolutely no idea how this increases security. Is the guiding principle here that hackers (or their computer algorithms) are somehow inherently lazy or give up easily?

(Interestingly, it would also appear that hackers only speak English. For instance, say your passphrase is something stupid like “Mypasswordispassword”. According to the Password Monster website, it ranks as very weak because it can be cracked in 0.02 seconds. But, use its literal German translation of MeinKennwortistKennwort and you won’t have to think up another password for the next 650 billion years. Hell, just use Kennwort alone and you’ll add 17 hours to the 0 seconds needed to crack “password”. Now, it’s widely said that German is not one of the easiest languages in the world to learn but really?)

The more defining step of true 2FA recently went online and, as proudly announced by IT’s “2FA Team” (and, yes, they are officially known as that), will be in full force as of this month. To avoid the hassle of constantly having to use an authenticator app, permanent staff were blessed in receiving a special dongle, to which the Mac person in me can only say, and then from the very bottom of my heart, “Great. Another fucking dongle.” We’re expected to keep this dongle safe and with us at all times, if not continuously plugged into our computer when we’re working with it. (Which is not easy when you’re using a laptop like me that only has two USB-C ports to begin with. Fortunately, however, my Mac somehow virtually swallowed the dongle so that I can access its functions via my password. This is actually very, very handy because plugging the dongle into my iPhone disables the keyboard from being shown in some apps on it and which is necessary during the whole process for typing in things like usernames. As such, the actual dongle is now languishing somewhere safe but not really with me, with its exact location entrusted to those same portions of my memory that I use to forget all my impossible passwords.)

So, with authenticator of your choice in hand, what was a comparatively simple two-step login—open the web page and have your device securely autofill the information—suddenly bloated to six: open the web page, fill in your username, select the 2FA method, fill in your password, get informed that you will be about to use a 2FA method, and finally really use that 2FA method.

And for our electronic teaching platform (StudIP, an anagram of stupid, BTW; just saying …), you can add a seventh step on top of that because the login page now defaults to one where you can select your status group for the login procedure: admins, people outside the University of Not-Bielefeld, or the 15 000+ members of the University for which the platform is actually designed (you know, those who actually do or, even more incredulously, receive the teaching?), who now have to click an extra box to even begin their official, patience-straining, but fabulously secure login journey.

Given those back-to-back home runs, it’s obvious that the IT Department recruited that 2FA-Team from the IT beer leagues. Seriously. How did anyone ever come up with that system and how did anyone else ever think that it was a good idea? Exactly none of the many other 2FA systems I have to use these days even use separate pages for the username and password because at least their IT people realize that it’s that secondary verification and not an endless number of webpages that is providing the security. Forget hackers, I don’t even want to log in to my own account anymore.

And the fun continues …

After that same hacker onslaught, all staff were required to install a sentinel program that apart from being a normal antivirus program also automatically monitors our computers for threats or other suspicious activities that are then blocked both on the computer and also centrally if need be. The former actually happened to me recently because of a threat that was menacingly identified as “persistence_deception” and which was severe enough that the sentinel program blocked my computer from accessing the internet anymore. But not to fear because the same program also provided me with the e-mail address and URL of our IT service desk for help, both of which are incredibly handy when you have no internet.

Fortunately there was also a phone number provided and it was quickly determined that the culprit was a program that I had just updated to its most recent version, namely Nextcloud. You know, Nextcloud, the program for file sharing and group documents that the University is forcing us to use instead of Google Drive? In any case, the IT person just sighed and said that they’d white flag it. (Probably again given that sigh.)

And then it all started from zero a few weeks later with the next Nextcloud update. In the end, my permanent solution was to simply stop using this University-approved program, which I always found to be a general pain in the ass anyway, and to go back to using Google Drive. I mean really. Let’s think about which is more likely to occur: a data breach at google or a(nother almost) successful hacking of the University’s servers, probably because someone wasn’t staying alert to that stupid e-mail banner and got reeled in by a phishing attempt in a split-second brain fart.

Again …