With lots of spare time this weekend because Easter means that everything here in Not-Bielefeld is either closed or illegal (including, of course, public viewing of the morally questionable 1974 Japanese anime production of Heidi, Girl of the Alps), my thoughts wandered back to the question of why Jesus seems to die on a different day each year. As it turns out, Good Friday this year does indeed fall on one of the two days when most scholars agree that he was crucified on (April 7th, the other being April 3rd) and I got to wondering how often that this was the case.

A quick bit of reading (AKA “research”) revealed even more quickly just how complicated the whole timing of Easter thing actually is. (As well as how many only vaguely relevant but still damn interesting rabbit holes Google can lead you down sometimes.) Most people know Easter as being the first Sunday after the full moon that occurs on or after the spring equinox (but actually, if inaccurately, fixed as March 21st). Or something vaguely like that. But, even after you wrap your brain around that definition to figure it out, it’s still only the end approximation of a long, drawn-out process designed to essentially standardize a variable date, in part by reducing its dependency on the Hebrew calendar (which seems to be even more complex). Despite the definition, Easter actually has nothing to do with a real full moon officially, which could cause it to occur on different days in the same year depending on where you are on the Earth. Instead, the Paschal computus formula developed by the Church to calculate Easter each year, the earliest known forms of which go back to at least 222 AD, uses a Paschal full moon, the 14th day of a lunar month. (The modern version of the formula uses golden numbers and epacts, both derived from the lunar cycle and is so complex, you wonder how anyone ever came up with it. Or how they could justify getting away from the Hebrew calendar on the grounds of simplicity in the first place.)

All so much simpler and directer than just using the actual day that Jesus died, now isn’t it?

(Perhaps a step in the right direction is an actual standing, but unenforced 1928 English law, last reaffirmed in 1999, that fixes Easter Sunday as the Sunday following the second Saturday in April. As such, Easter would still wobble, but only between April 9th and April 15th, making it much more of a typical British fix than a German one.)

Formulas but not full moons aside, the problem with the timing of Easter is just that: it is determined in part by the moon, the timekeeping functions of which are, at best, limited to delimiting how long a month is. (But realistically “at worst” because it does a pretty crummy job at it for most months. It also doesn’t help that the length of the lunar cycle itself varies by nearly two days depending on your frame of reference, the moon’s (sidereal) vs. your’s (synodic). (The latter is also true for the length of the year, but the difference there is only about 20 minutes, which for me is close enough to the annoying academic quarter that it too should simply be ignored.) As such, Good Friday can fall anywhere between March 20th and April 23rd in any given Gregorian year.

But I got to wondering how often it fell on any given day in that 35-day period and, in particular, on those two days when most scholars agree that Jesus actually died?

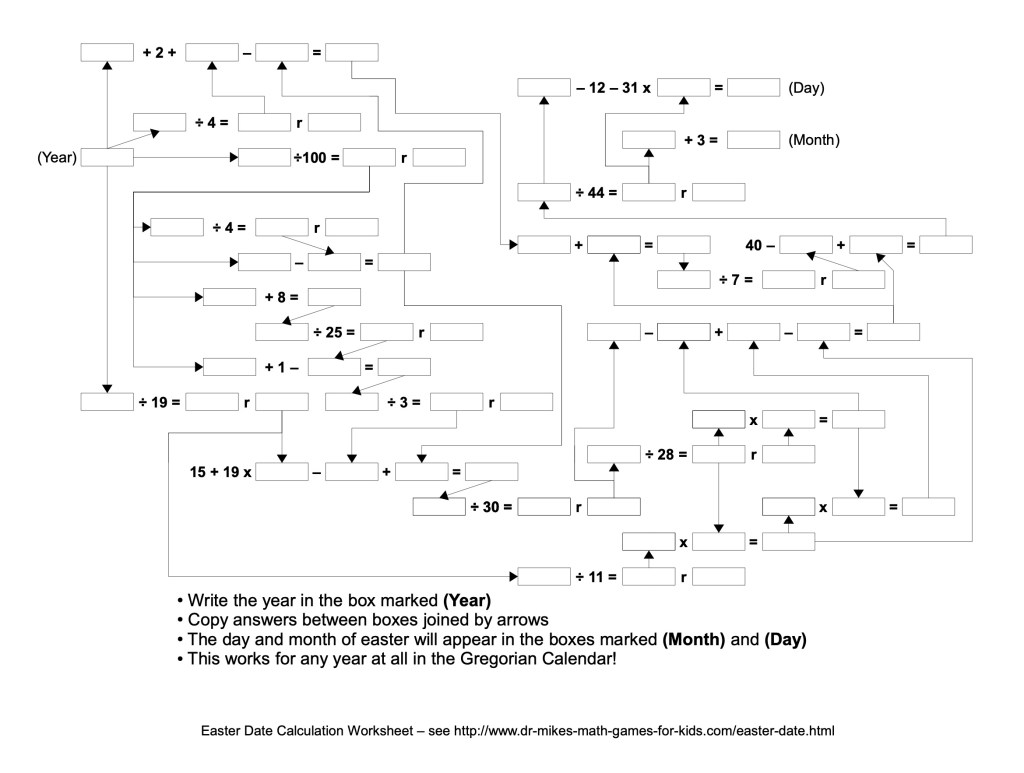

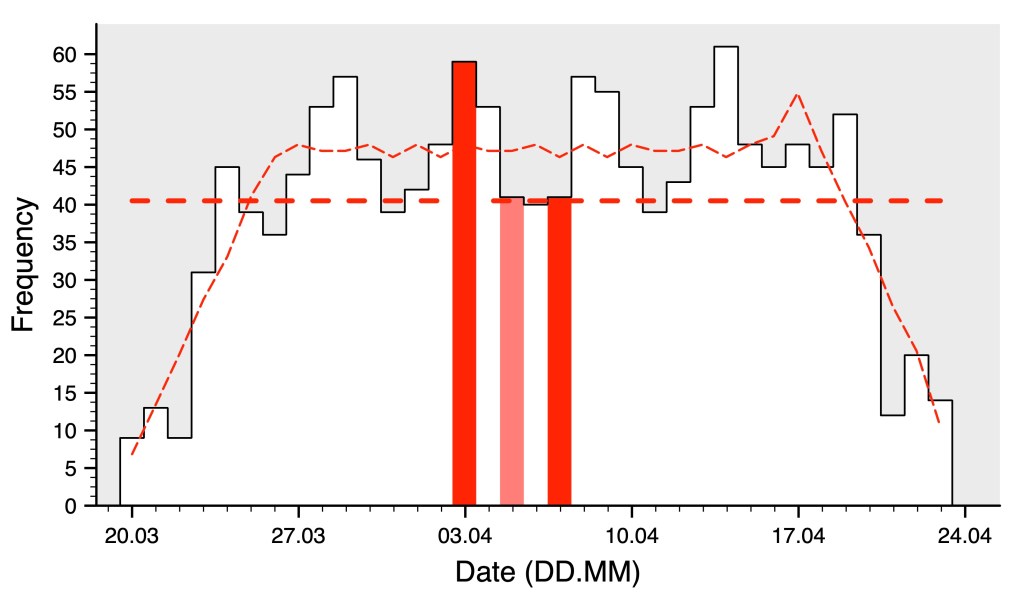

Using data from Robert Harry van Gent (and there are many, many other such webpages; seems I’m not alone in my weird thoughts …), I plotted just how often Good Friday has occurred on any given day from 1583 to 3000 AD. (The odd starting year is because it’s the year after the Gregorian calendar was mandated into use by Pope Gregory XIII. And, yes, I realize that all the data and all the formulas are for Easter Sunday, not Good Friday. I just see the latter as having temporal, if not logical, priority. Hard to have a resurrection without a crucifixion after all. Just add two to all the dates if you disagree.) Immediate hindsight told me that this should all be a non-issue. All things being equal, each of those 35 days have just under a 3% chance of being Good Friday.

But, of course, all things are not equal …

For starters, the first and last weeks get progressively shortchanged for similar, but different reasons related to boundary effects. For Easter to occur in the first week, the (Paschal) full moon and the equinox have to line up just right or else the Easter bunny thinks it’s a groundhog and snoozes toward the middle of the window. By contrast, the last week has to hope that Easter hasn’t already gotten a better offer beforehand.

But, even when you get past the boundary areas, Good Friday still hops around a good amount to play favourites (e.g., April 3rd, but not April 7th). Again, all things here being equal (no boundaries anymore …), Good Friday should fall on each day about 48 times, but its real distribution is instead surprisingly large, ranging from 36 to 63 times per given day. It must be said, however, that these 1418 years are only a small sample that are absolutely nothing compared to the total of 5 700 000 years (and not just “about 5 700 000” but exactly 5 700 000) before the whole cycle starts up again.

And even in that complete, quasicrystallic Easter cycle (thanks again for the data, Robert), although the thin red dashed line has flattened out a lot, there’s still quite some bounce left in it that shows a curious periodicity of two to three days??? (For those more curious than this periodicity, April 3rd is riding the top of its local wave and April 7th the bottom, with my compromise of April 5th being a really well-behaved compromise by being right in the middle.) But then the last mini-cycle before the boundary disappears in favour of building to a unique mini-spike of 23 000 extra times for April 17th, 29 days (or pretty dead on one (synodic) lunar cycle) after the spring equinox starting off the whole exercise.

Umm, right …

I think I learned something, although not necessarily the answer to what I was asking this weekend. And, although the timing of Easter has the fingerprints of admin all over it, there’s not really much admin being talked about here today. (Sorry about that.) I guess it could count as a bonehead calculation of the day (BCD), but even that’s stretching it. (Ok, I stretched it.) Maybe spare time on my side isn’t necessarily such a good thing after all …